This content is also available in video format in this playlist.

Introduction #

Awareness of Bitcoin’s value proposition for censorship resistant payments took off in 2011 with the launch of Silk Road and the rescue of the otherwise donation starved Wikileaks.

Simultaneously a dangerous and inaccurate narrative surrounding bitcoin transaction privacy took off: “anonymous” payments.

WikiLeaks now accepts anonymous Bitcoin donations on 1HB5XMLmzFVj8ALj6mfBsbifRoD4miY36v

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) June 14, 2011

This perception was never true and largely due to a lack of understanding of bitcoin’s underlying functionality. Further, almost no one was watching the blockchain in 2011. But the blockchain is forever.

Today law enforcement’s access to chain analytic tools has aided in many high profile take-downs. Chain surveillance firms clamor for first publication of blog posts on the latest “crime” using bitcoin for payment. The mainstays of old media are running headlines on bitcoin’s traceability.

Bitcoin is Traceable Headline

Traceability is mainstream. #

The reality of bitcoin privacy, and what users are capable of when using bitcoin to make payments, lies somewhere between perfectly anonymous and perfectly traceable.

Most tracking techniques are reliant on heuristics and evaluating the flow of bitcoin. Without fundamental privacy enhancements at the protocol level, these techniques must be undermined at the application layer.

Early in bitcoin’s history, randomized wallet fingerprinting was used to defeat analytic heuristics. Tools such as custodial tumblers were used to defeat financial flow analyses at the risk of loss of funds. Today coinjoins and collaborative transactions allow for reasonable spending privacy with enhanced security over previous methods. However, much work remains to be done in automating privacy enhancements at the application layer.

We consider education among the remaining work to aid users in obtaining a basic level of financial privacy they are typically afforded by the legacy financial network. This is our main motivation for creating this documentation. In this guide we will cover the following:

- What “traceable” bitcoin really means including examples.

- Defensive measures users can take to defeat tracking and why they work.

- Practical considerations for users sending and receiving payments.

Problem Statement — Pseudonymous Bitcoin #

Bitcoin transaction activity is pseudonymous, not anonymous. A user’s true name and personal identification information (PII) is not included in the Bitcoin protocol. This provides a very basic level of privacy, as transaction activity must be attributed to an individual.

However, bitcoin transactions are made for transparent amounts to transparent addresses. Addresses are pseudonyms that represent an actual user’s activity, or more specifically, a private key’s activity.

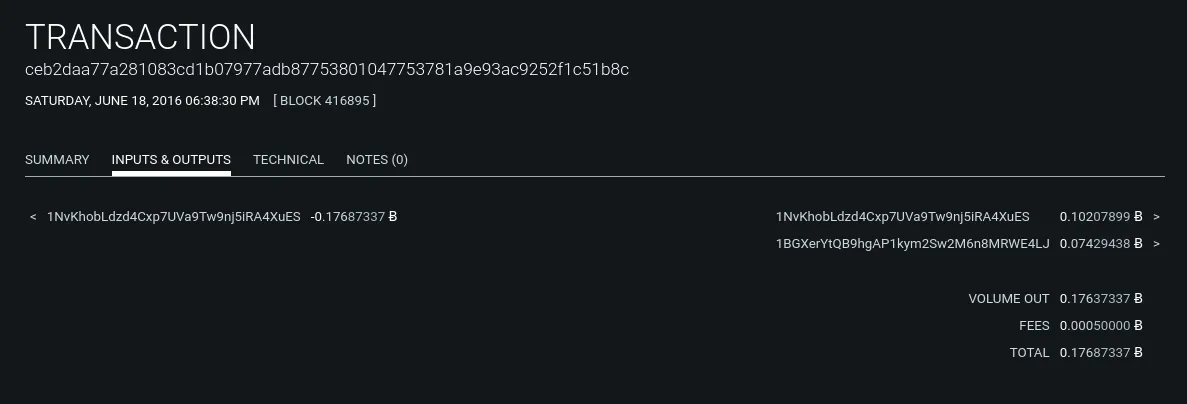

Example Bitcoin Transaction

Bitcoin transactions are broadcast to the bitcoin network, and archived on the bitcoin ledger. The ledger, and any transactions included in the ledger, are viewable to anyone running a bitcoin node or with access to a web based blockchain explorer.

The transparency of this public information allows for an unprecedented ease of information access that is not possible with the traditional financial system.

Users can query a blockchain explorer through a web browser and observe the entire bitcoin network’s past transaction history. They can easily track the flows of bitcoin across multiple transactions.

Broadly, this practice has become synonymous with the terms traceability and chain analysis.

The most common form of chain analysis is focused on identification of transaction “change” outputs. The process is based on a series of heuristics that can be used to follow a user’s activity over multiple transactions.

If this on-chain activity leads to an identified economic entity’s wallet cluster, investigators may be able to obtain user PII associated with the observed transaction activity.

From here we can glean two critical issues that can be used to attack a user privacy:

- “Change” outputs can be used to track a users activity on the blockchain.

- The intersection of this activity with entities that obtain PII links observed blockchain activity with a possible real identity.

While item 2 is a critical part of what turns chain analysis into real world enforcement, this documentation will focus specifically on mitigation of the on-chain tracking.

Heuristics #

Heuristics are rules of thumb used to make decisions under uncertain conditions. They are often based on practical shortcuts. Being shortcuts heuristics are not 100% accurate.

Much of traditional chain analysis is based on heuristics. The primary heuristics have to do with “change detection” in simple spends and the clustering of separate addresses by the common input ownership heuristic.

In isolation, these heuristics can be misleading and inaccurate. But when combined with additional transaction patterns or external data such as wallet cluster labeling, the short comings of these heuristics become less damaging to attempted tracking.

Unspent Transaction Outputs (UTXOs) #

Bitcoin transactions are records of the flows of bitcoin between addresses.

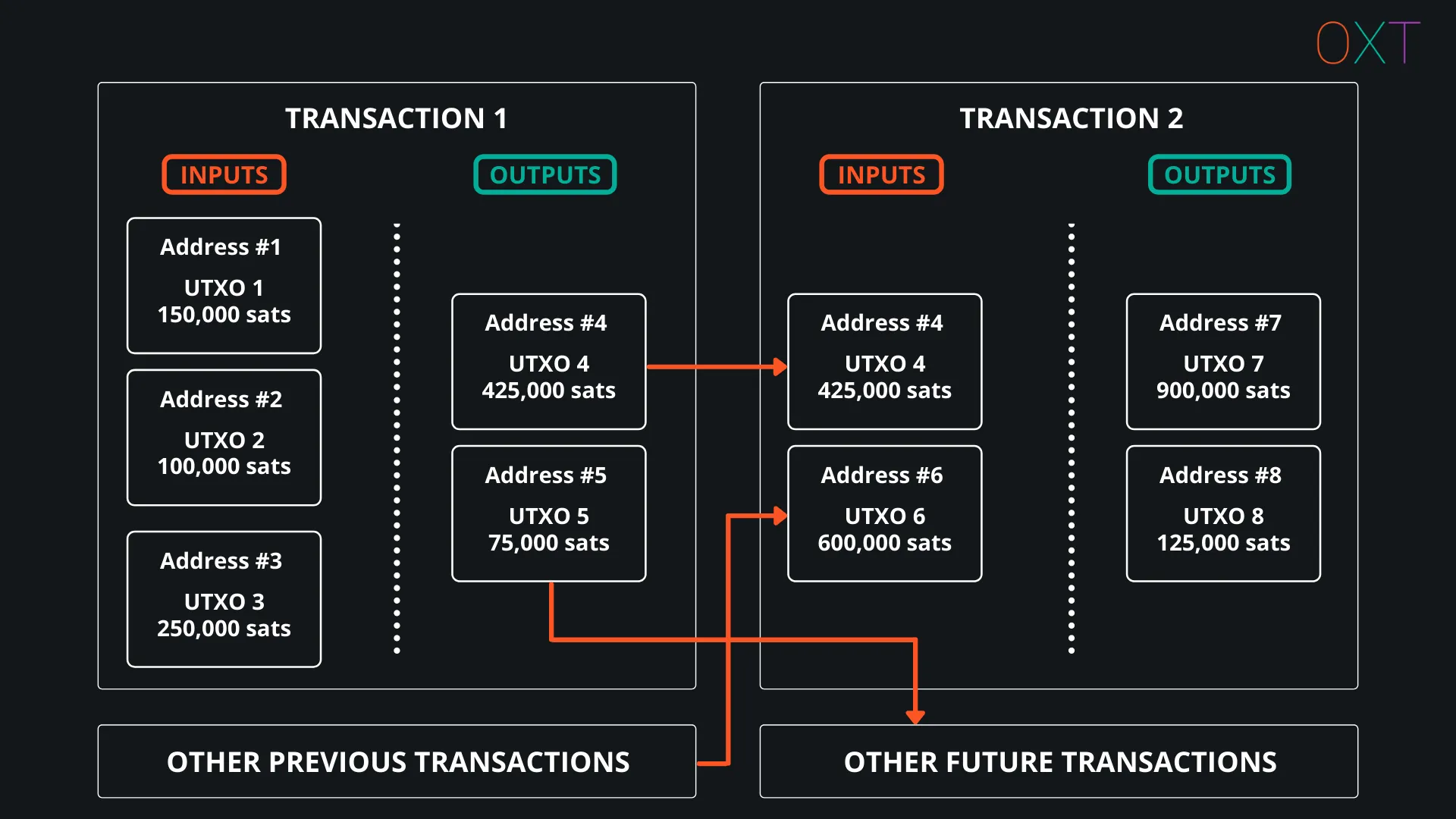

Unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs) are “pieces of bitcoin” that are used to construct transactions. Transaction structure can be divided into inputs and outputs.

A user constructs a transaction by designating a payment address(es) and payment amount(s). These will be the outputs of the newly constructed transaction.

Typically wallet software will complete the transaction by algorithmically including UTXOs from previous transactions as inputs to the new transaction.

Unspent Transaction Outputs (UTXOs)

There is a difference between an address and a UTXO. UTXOs are “pieces of bitcoin” paid to an address. The simplest way to visualize the difference is to understand that an address can receive multiple UTXOs, a process detrimental to privacy referred to as “address reuse”.

Example Transactions #

There are several common categories of bitcoin transactions. These categories are inferred based on a transactions input and output profile along with our experience and observed cluster labeling. Examples of the major transaction types are provided below.

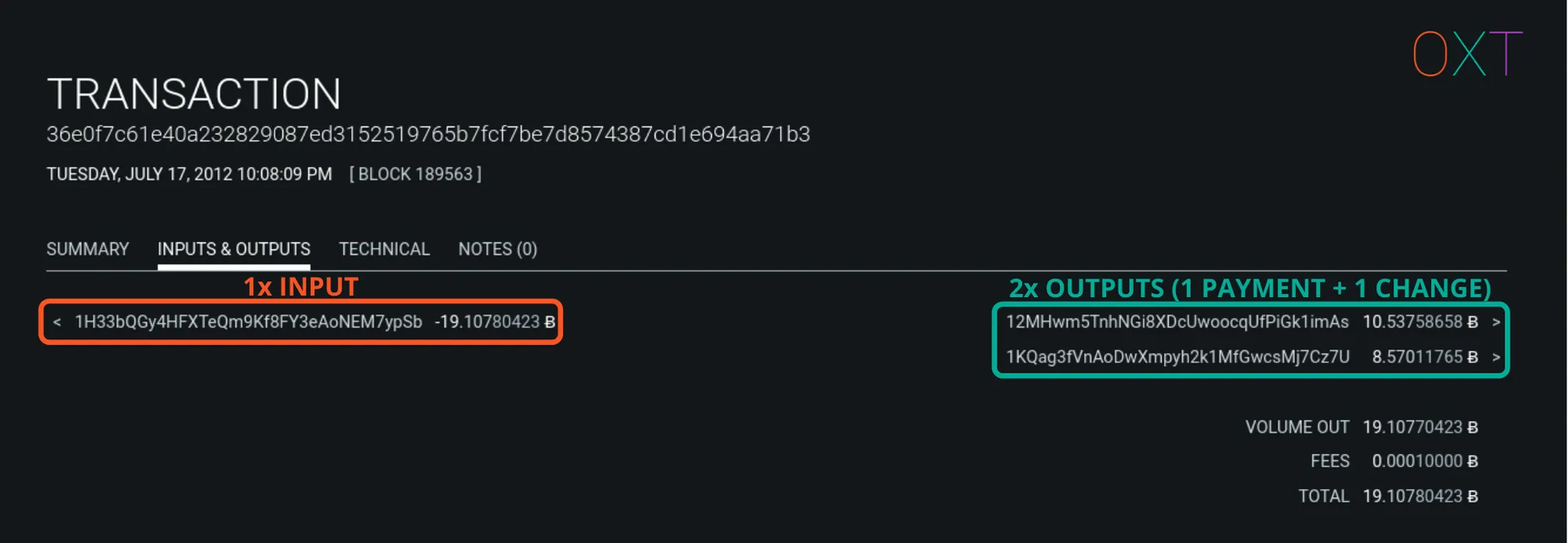

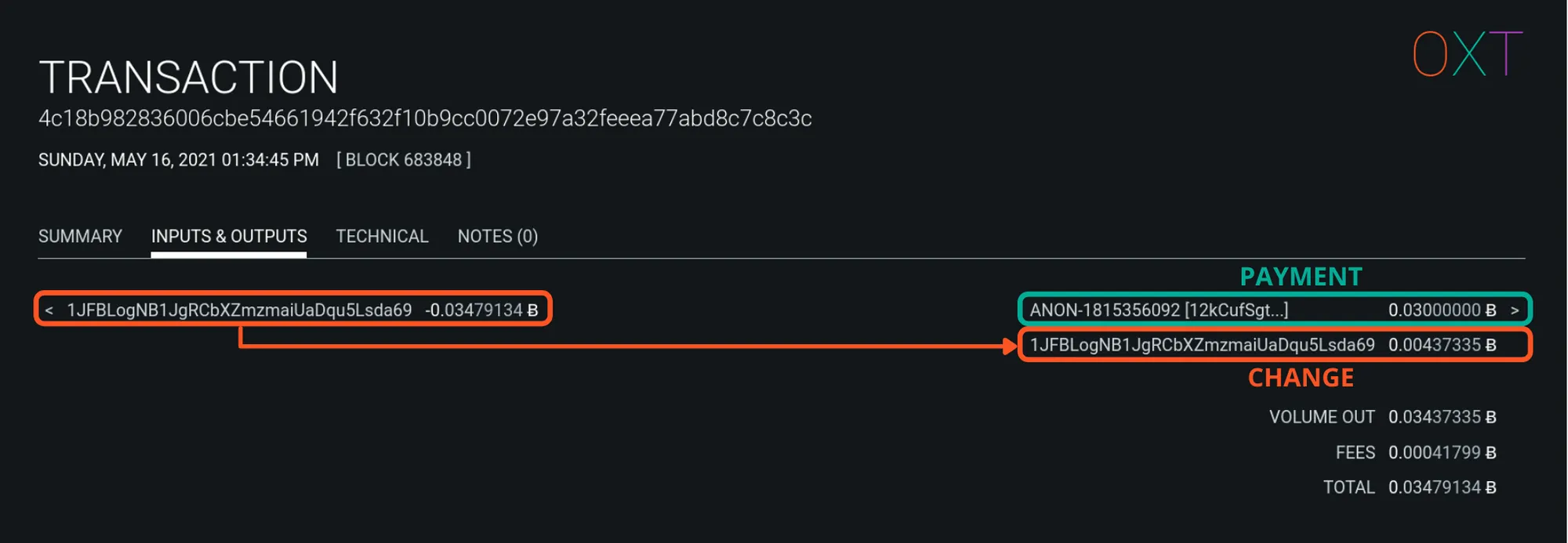

Simple Send #

Simple spends are some of the most common transaction types and make up roughly 50% of bitcoin transactions in recent blocks (Source: transactionfee.info).

These transaction types are evidence of typical user behavior, where a user makes a payment and receives a change output.

Traits:

- Number of Inputs: 1 (or more)

- Number of Outputs: 2

- Common Interpretation: 1 payment output, 1 change output

Simple Spend Transaction Example

Sweep #

“Sweeps” spend the entirety of a single UTXO to a new address.

Traits:

- Number of Inputs: 1

- Number of Outputs: 1

- Common Interpretation: Possible self-transfer

“Sweep” Example Transaction

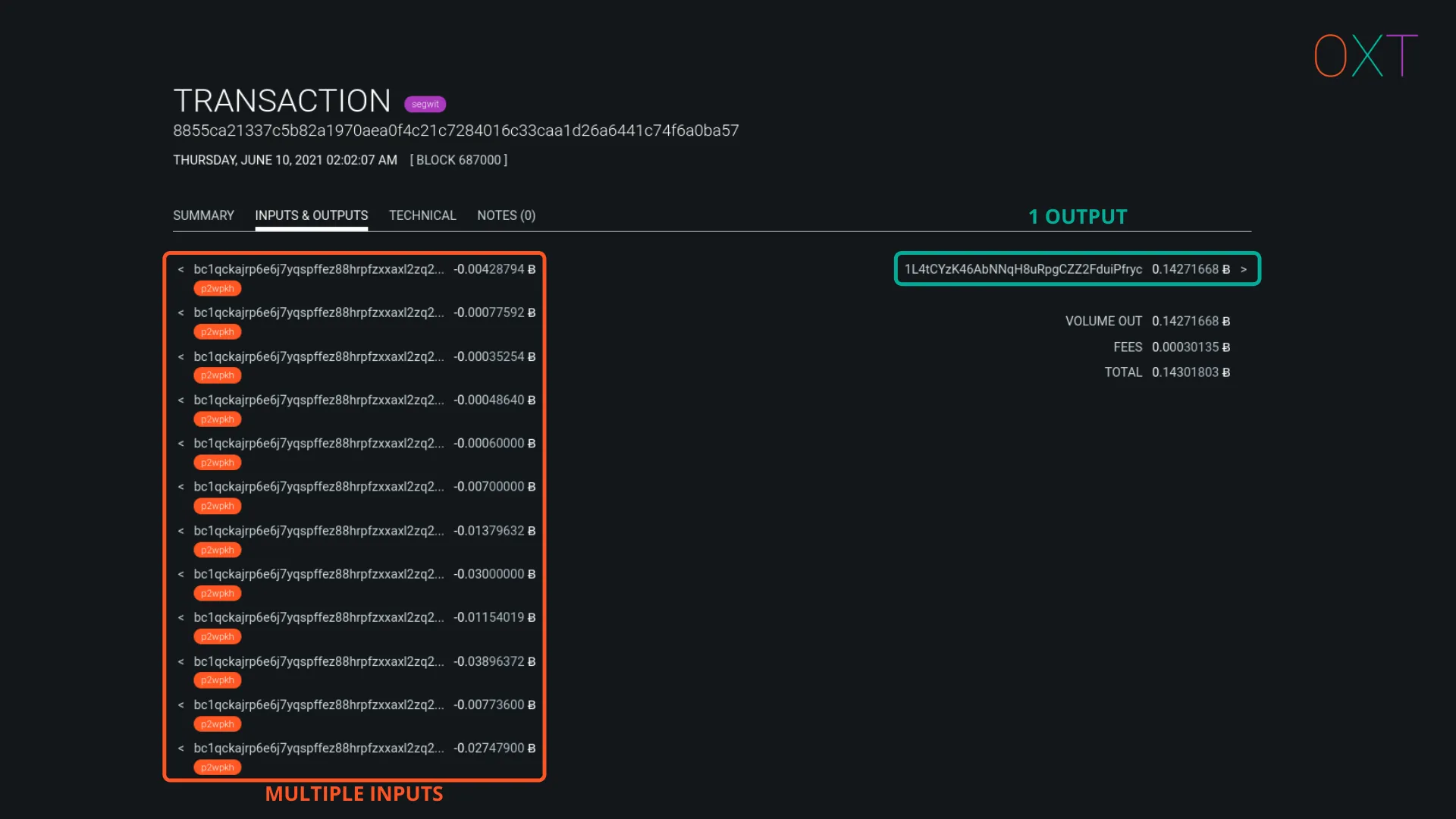

Consolidation Spend #

Consolidation transactions combine multiple UTXOs into a single UTXO. These are rarely “true payments” because a normal payment has a change output.

Traits:

- Number of Inputs: >1

- Number of Outputs: 1

- Common Interpretation: Possible self-transfer

Consolidation Spend Example Transaction

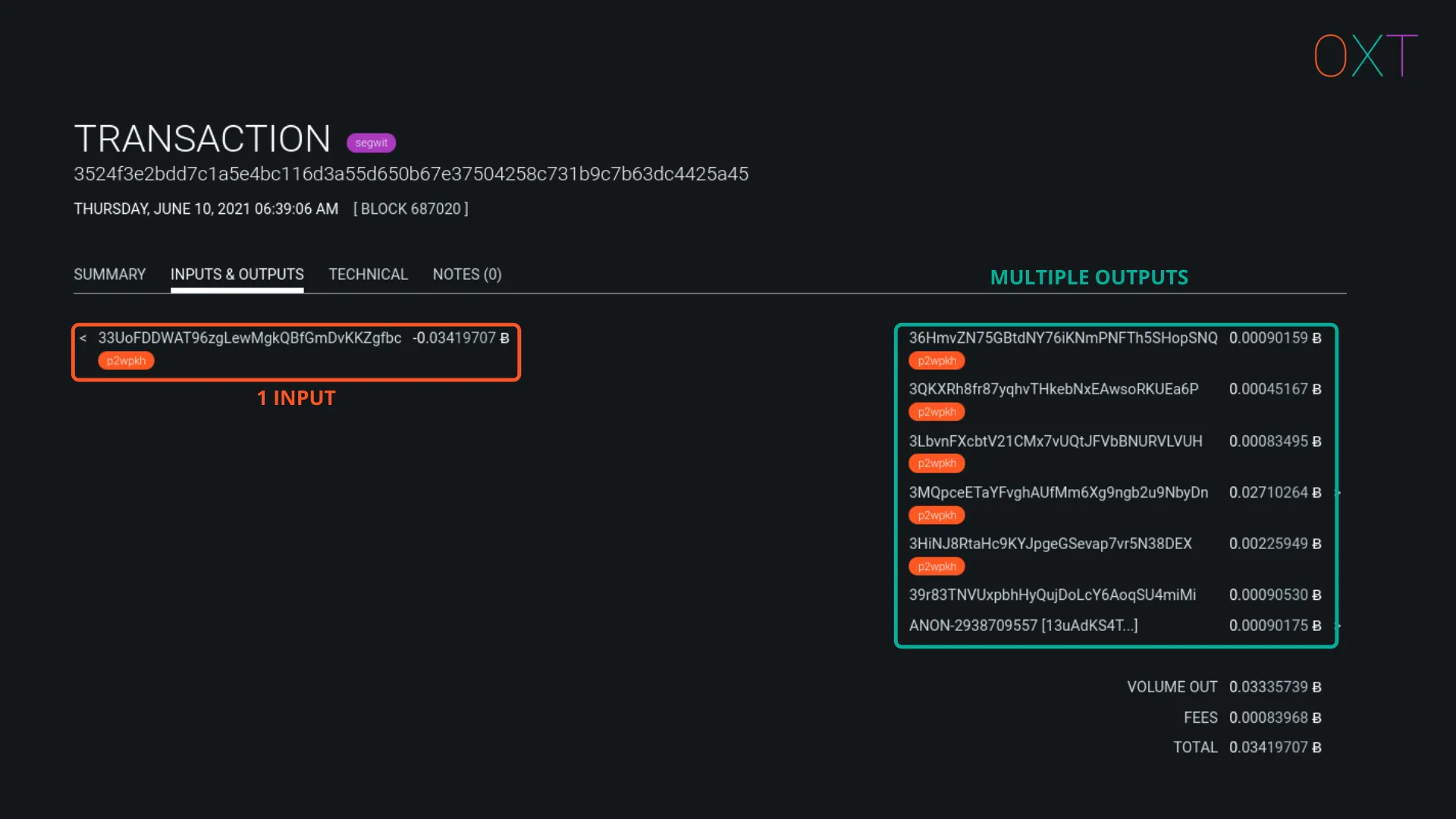

Batch Spend #

Batch spends are most likely performed by exchanges and include 1 or more inputs and many outputs. These transactions aim to save on miner fees by making as many payments as possible in a single transaction.

Traits:

- Number of Inputs: ≥1

- Number of Outputs: MANY

- Common Interpretation: Large economic activity, likely exchange

Batch Spend Example Transaction

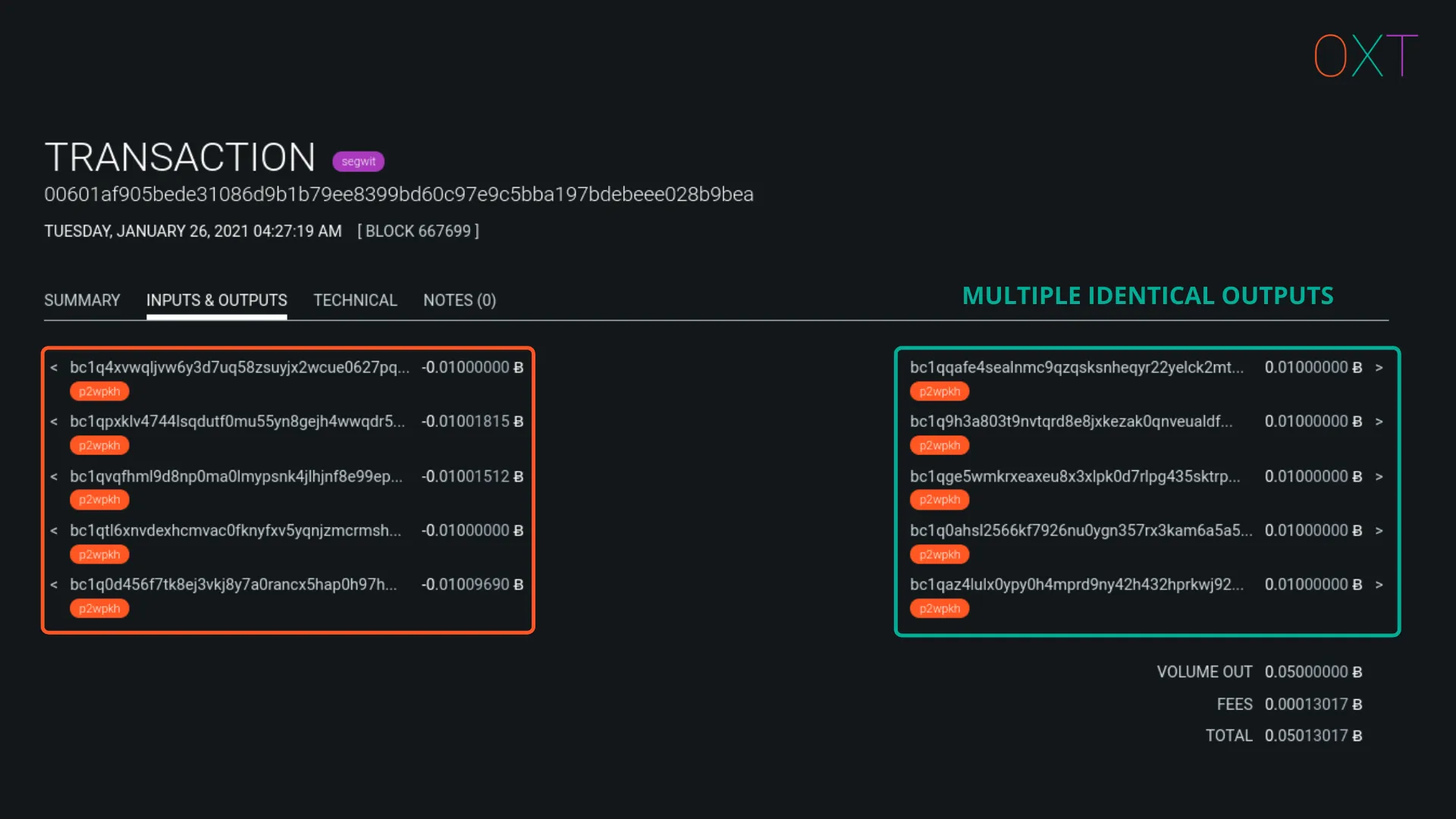

Multi-party Transactions (Coinjoin) #

Multi-party transactions involve collaboration between many users to perform a single transaction that improves participant privacy. These transactions are easily identified by their equal output amounts.

Traits:

- Number of Inputs: MANY

- Number of Outputs: MANY

- Output Profile: Number of identical outputs is a proxy for number of participants.

Coinjoin Example Transaction

Change Detection — Simple Spend Interpretations #

In this section we are going to introduce transaction interpretations for simple spends (1 input, 2 outputs). This section will focus on the most common interpretation of these transactions, where one output is interpreted as a payment and the remaining output is interpreted as change back to the original wallet. A complete list of interpretations under this model are presented in Part III. The goal of this section is to familiarize the reader with the heuristics used to evaluate simple spends and detect a change output.

When observing a single transaction in isolation, we are presented with a limited amount of data that is included within the transaction. We refer to this information as internal transaction data.

Internal transaction data is limited to the following:

- amounts (input, output, miner fees)

- input address script type

- output address script type

- transaction version number

- transaction locktime

- replace by fee signalling

Change Detection #

Due to miner fees, a normal bitcoin payment always requires spending a larger output amount than the intended payment amount.

When a single UTXO for a larger amount than the intended payment amount is consumed, the user will receive a change UTXO for the remainder back to an address generated by their wallet’s private key.

Much of traditional chain analysis is based on detecting this change output. If a change output can be successfully detected, a single user’s activity can be tracked across a series of transactions.

In this section we will detect change outputs based on internal transaction data. The heuristics are presented roughly in the order of decreasing effectiveness accuracy. Examples will be presented and annotated screenshots shown for aiding users in visualizing these concepts.

Address Reuse #

Addresses are created by a single private key. Multiple uses of the same address are signs of activity of the same private key.

In a simple spend, if one output is to a new address, and the remaining output is to the same address as the input address, we know that the reused address is the change output.

Today, most bitcoin wallets will automatically generate a new address for receiving change outputs. However, a wallet can be configured to receive change to the same address as the transaction input. This behavior is typically indicative of centralized service wallet activities or old versions of the bitcoin core wallet.

Address Reuse Example Transaction

Round Number Payment Heuristic #

When a user initiates a payment, they input the payment destination (address), payment amount, and a network transaction fee into their wallet software. The wallet software will select input UTXOs and generate the change output (if there is one).

The change amount in a simple spend is calculated as follows:

input amount ➖ payment amount ➖ tx size (in vbytes) ✖️ network fee rate (in sat/vbyte)

It’s difficult for a user to generate a change output for a “round number amount” on purpose. In a simple spend, the round number output is the likely payment which makes the remaining output the change output.

Round Number Payment Heuristic Example Transaction

Different Script Type Heuristic #

There are several bitcoin address script types. Readers will be most familiar with the following script types:

- Pay to pubkey hash (P2PKH): Addresses starting with a 1

- Pay to script script hash (P2SH): Addresses starting with a 3

- Native Segwit (version 0)(bech32): Addresses starting with bc1q

For a given input script type, if one output is to the same type as the input and the remaining output is to a new address script type, the output to the new address script type is the likely payment. Which makes the output to the same address address script type the likely change output.

In other words, an output to a different script type is the likely payment output. This heuristic can also be combined with the round number payment heuristic.

Different Script Output Type Heuristic Example Transaction

Largest Output Amount Heuristic #

Another simple heuristic, assumes that the largest output amount is the likely change output. This is one of the weakest heuristics, particularly when taken in isolation, but as we will discuss in Part 2, this heuristic can be helpful in a transaction graph analysis.

Largest Output Heuristic Example Transaction

Review And Preview #

In this section we introduced many of the basic concepts around bitcoin transaction privacy. Pseudonymous bitcoin provides a basic level of privacy that is not directly associated with personal identifiable information.

However, the openness of the bitcoin protocol allows for the tracking of bitcoin flows. This concept is broadly referred to as “chain analysis”. A core focus of chain analysis focuses on detection of change outputs by making use of several heuristics. If successful, these heuristics allow for tracking a single users activity over multiple transactions.

Part 2 will introduce core concepts of chain analysis such as:

- External transaction data, which can be used to weaken transaction privacy.

- Transaction graph analysis, a main tool for tracking the flow of bitcoin over multiple transactions.

- The common input ownership heuristic, also known as “wallet clustering” and its implication on the bitcoin network.

- This section also includes a walk-through and examples of OXTs transaction graph tool and wallet clustering scheme.

Part 3 cover core concepts of improving bitcoin’s privacy including:

- Randomized wallet fingerprinting for defeating change detection.

- UTXO flows and the fundamental link between inputs and outputs.

- How equal output coinjoins address the issue of deterministic flows.

- Transaction entropy

- How payjoin defeats the common input ownership heuristic

Part 4 discusses:

- Analyses needing a “starting point”

- The privacy implications of sending and receiving payments

- How existing privacy techniques can mitigate many of the issues discussed throughout the guide.